If our perceptions of the world cannot be absolutely proven as accurate, can we still be conscious? We centered many of our early ideas on Descartes’ rejection of the exterior world, focusing on his non-reductionist conclusion that consciousness is a feature of the mind and not the brain. Despite Descartes’ rejection of physical perceptions, he still emphasizes exposures to experiences as fundamental to achieving sentience.

Influenced by Descartes’ discussion of the inability to prove the validity of sensory inputs, we initially posited that phenomenality was not significant to his conception of consciousness. We now realize that we had an oversimplified understanding of this quality of consciousness: we initially regarded phenomenality as a unique experience achieved only through exposure to sensory stimuli. Further reflection upon what might prompt a conscious experience allowed us to realize that phenomenal experiences can occur within the confines of the mind, irrespective of any external factors.

The cogito and Descartes’ experiences with doubt are themselves phenomenological experiences. The associated feelings characterize what it is like for Descartes to be conscious within his own mind. More important than the objective fact that he is thinking or doubting, it is Descartes’ experience of thought/doubt allows him to prove his own consciousness. While Descartes’ discrediting of the exterior world remains a central feature of Meditations, we now understand this does not eliminate phenomenality’s existence from the work. Where we had once only thought of emotional phenomenality, we were now able to comprehend intellectual phenomenality. Broadening of our conception of phenomenality led us to further consider other concepts that we had initially discounted, such as the role that senses might play in consciousness.

While Descartes may assert that his perception of the outside world cannot be trusted, there remains some value in his ability to observe it. Exposure to experiences allows Descartes to gain understanding and progress toward sentience. Descartes’ sensory observations provide frameworks for understanding and gaining insights about key world truths. For example, even if objectively false or placed in his mind by an evil demon, Descartes’ observations of the melting wax help him to gain an understanding of complex ideas like the passage of time and extension of objects. These are ideas that he may not have been able to conceive of without his visually-based thought experiment, meaning sensory experiences have some value for learning.

The relevance of the senses can be tied to another part of Descartes’ discussion of consciousness: memory. Without emotion, each memory would be similar to a movie scene, much like how the unawakened hosts recall their cornerstone memories, in a manner both objective and detached. Sensory experiences, reliable or not, prompt emotions within us that shape our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. These experiences and associated emotions are stored as memories. Considering that each individual’s self concept is memory-based, it logically follows that memory formation extends beyond the objective facts of the event.

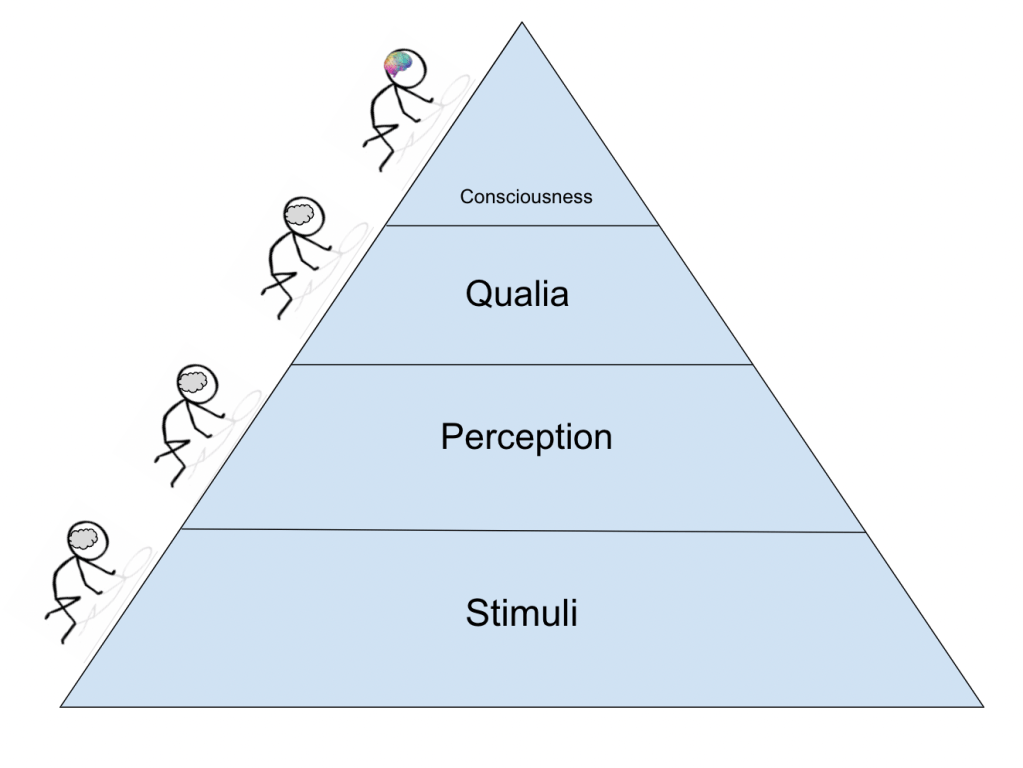

Emotions are a phenomenological experience; how it feels to be happy or sad in one’s mind shapes a large part of what it means to live as that individual. It is this unique aspect of emotion that allows memories to affect and shape one’s consciousness. Even if a group of people share the same experience, they will all experience the emotions surrounding it differently and form unique memories of it. By extension, each individual will assimilate the experience into their self differently. These individualized experiences of senses and emotions create layers of memories and awareness within our identities over time. Despite claims of possible deceit, this experience of “being me” through our senses cannot be denied.

This line of thinking allowed us to recognize reflexivity as the quality that most closely applies to Descartes’ reasoning. Awareness of one’s thoughts intimately resembles Descartes’ “cogito, ergo sum.” Therefore, this quality of consciousness is important to help us understand the crux of Descartes’ arguments surrounding consciousness. Considering reflexivity also raises questions about how consciousness is achieved. What instances promote awareness of one’s thoughts? Is gaining consciousness a bifurcation or continuation of one’s life?

We have established the ability of the outside world to influence our understanding of larger concepts and impact our conceptions of self, yet we still have no way to ensure reliability of sensory perceptions. So, can we reconcile our notably inaccurate perceptions with our status of consciousness? We must remember that perception is reflexive: it derives from the understanding of objects rather than from those objects themselves. Therefore, it is not the accuracy with which we perceive reality that makes us conscious, but our ability to know that we are perceiving. In a way, this makes us like Westworld’s hosts: even if we’re living in an alternate reality, we can still be conscious.